October 2020

Welcome to the October 2020 edition of the Digital Technologies in focus (DTiF) newsletter. While the Digital Technologies in focus project needed to adapt due to COVID-19 travel restrictions, it’s great to see that many schools have continued their Digital Technologies journey. Learning from home has taken on a whole new meaning for one member of our team. Simon Collier went on holidays with his family just before the Victorian lockdown, so he has been supporting his schools from the Far North Coast of NSW in Term 3 while home-schooling his two school-aged students and a preschooler. He has been providing online professional learning for teachers and teaching lessons online with some of the students in his Melbourne DTiF schools. Simon has been really impressed by the adaptability of both students and teachers.

Other curriculum officers have been able to travel within the state that they live so it’s been great to hear of the enthusiastic engagement of schools. Peter Lelong is visiting Tasmanian schools for one last time before he finishes up in December; Martin Levins has been intensively supporting New England, NSW, schools but also connecting online with his Top End Remote schools; Sarah Atkins has visited her schools in the Burnett region, Qld; and Shane Byrne has been clocking up the kilometres from Taree to Trangie in NSW.

The DTiF in conversation has been running at 4 pm AEST on Wednesdays and will continue in Term 4. It’s been great to see teachers sharing their experiences of implementing Digital Technologies. If you are interested in sharing your DTiF story, contact Sarah Atkins [email protected]. See the DTiF wiki for more information on session times and topics and to catch up on webinars you have missed https://bit.ly/acarawiki. The webinars are converted to podcasts for quick access.

Regards,

Julie

Julie King

Project Lead,

Digital Technologies in focus

Do you have some feedback on the newsletter and/or topic suggestions? Provide your ideas through your local curriculum officer, or via email [email protected]

DTiF webpage

The DTiF webpage, located on the Australian Curriculum website in the ‘Resources’ section, has been updated with even more new content to give you great ideas for 2020. This month we have added a collection of webinars from well-known academics and experts in the field of education and computer science, such Dr Michelle Ellis, Dr Tim Bell and Prof. Stephen Heppell. Each webinar begins by illustrating the connection of the talk to the key concepts of the Australian Curriculum: Digital Technologies and is recorded to enhance your individual or staff professional learning. Some webinars are interesting talks by these engaging speakers, others are tutorials or demonstrations.

Professor Stephen Heppell discusses research around a digital device he developed. The device is called Learnometer and is designed to measure environmental factors that can impact learning (figure 1). See the DTiF programming and algorithm resources on the Australian Curriculum website if you would like to create your own digital solutions to do this.

Dr Michelle Ellis shows the Makerspace dual programming environment, developed by Edith Cowan University, along with all the available teaching and learning resources (figure 2).

Figure 1 Figure 2

To access these talks, visit the 'Professional learning' section of the DTiF website and choose ‘Webinars’. While you are there, be sure to take a look in 'Other professional learning' for a selection of literature reviews on a host of Digital Technologies related topics.

What’s new?

Have you seen our tutorial resources? Resources include a guide to make a simple maze game using visual programming in either Scratch 3.0 or its older version 2.0. This is a good tutorial for beginners and it is also useful for pairs of students working together. Available to download and print now on the Australian Curriculum website.

DTiF video series

The team has been busy recording a series of videos to support teachers. They can all be found on the ‘DTiF in conversations’ pages. Series topics include:

- online learning

- types of thinking

- literacy in Digital Technologies

- numeracy in Digital Technologies

- visual programming

- key concept – digital systems

- DTiF in conversation

Spotlight on Casino West Public School

by Sarah Atkins

A small school on Bundjalung Country in New South Wales is doing mighty things with Digital Technologies. Casino West Public School’s school motto is ‘Dream. Believe. Achieve’. The staff and students are a living proof that they take their motto seriously.

Dee Taylor, ICT Lead and Stage 2 teacher, and Margie Savins, Stage 2 teacher, have led the school on a journey of discovery and rich learning since they joined the Digital Technologies in focus project in 2017. They began with a focus on improving creative and critical thinking with their Years 3 and 4 students, but soon recognised that the whole school was watching and was eager to participate.

Dee upskilled teachers by providing frequent professional learning. The school timetabled regular Digital Technologies lessons that involved all staff. As a result, teachers soon began using digital technologies in their own classrooms more often. Year 2 teacher, Karen Campbell, was excited by the possibilities for enhancing literacy with her students,

These technology lessons have been excellent … in between our lessons with Dee, I've been able to review the skills that she'd taught us, help the kids update their skills and practise mine. We've also used Scratch Jr in our literacy rotations and the kids have been outstanding in terms of the way they utilise the skills that Dee has taught us.

Implementing a Digital Technologies program is not without its challenges. Margie Savins commented,

One of the main challenges that I think our staff have found is … just finding time that's required to be able to play with the technology and to become more confident with it. An issue that we've had to overcome has been: how do the teachers in the class have easy access to the technologies?

Julie Ewart, the school’s business manager, explained how the school addressed access,

Our school has invested in 21st century learning … we have spent 60 thousand dollars on Chromebooks … it's gone so well that we're buying another 20. The project is aligned with professional learning of teachers … and through that teacher learning it has filtered down into the classrooms … students are getting a lot of enjoyment out of using this with the curriculum.

Students are now engaging in regular Digital Technologies activities in all learning areas, with a special focus on numeracy and literacy. Here is what one student had to say, “In our classroom, we learn with technology, we code with technology, we have fun with technology … it's been a lot of fun”.

So how will the school ensure their efforts continue into the future? Margie commented on the sustainability of the project,

Our participation in the ACARA’s Digital Technologies in focus project has been a fantastic platform for our school, and it's highlighted the importance of Digital Technologies in our classrooms. One of the many surprises … was the formation of a strong Digital Technologies team and we have members from every stage and all levels of staffing. I'm feeling that with the support our staff, our students will continue their Digital Technologies learning journey.

Listen to the full school reflective podcast

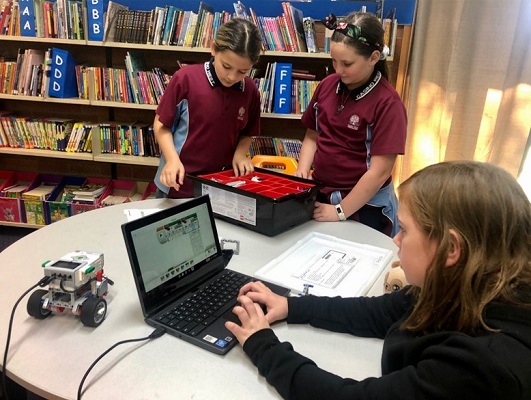

Students at Casino West Public School exploring robotics and digital technologies in literacy activities

Does the internet use much energy?

by Martin Levins

A July 2019 report by the Shift Project, a French thinktank, said streaming was responsible for more than 300 m tonnes of CO2 in 2018, equivalent to all of France’s emissions. Netflix streaming, they concluded, uses the same amount of power as the United Kingdom.

However, in its 2019 report on its environmental social governance, Netflix showed that the total electricity usage was about one-thousandth of the amount claimed, and 100 per cent of its electricity was from renewable sources anyway.

How could we check the claims made in these reports? It’s fairly complicated, but let’s have a go with a ‘back of the envelope’ calculation. We’ll discover how the internet works, as it is a good by-product.

Let’s start with something simple – email. What happens when I press ‘Send’?

My digital system needs to know where the machine that will accept the message (a mail server) is and then find out how to get there.

Let’s look at a typical process: you use Gmail and want to email your friend, on BigPond.

Your email needs to be sent to your email server initially, then to be sent on to your friend’s email server where it will be stored until it accesses the inbox.

Sounds easy: my system sends an email to [email protected], which then forwards the mail onto bigpond.net.au.

How does your computer know how to get to the Gmail server? Computers only work with numbers, they don’t understand names – so bigpond.net.au or mail.google.com means nothing to them.

So something needs to turn mail.google.com into a special number called an internet protocol (IP) number, much like directory assistance that gives the number of someone’s phone. Like a phone number, with country code, area code, regional code and then service number, the IP address is segmented into four groups separated by full stops. Once the number is known, the message can be routed to its destination.

This lookup is carried out by a domain name server, usually shortened to DNS.

My computer knows, from its Telstra network setup, that its DNS number is 1.1.1.1 – so my home router asks Telstra router to find the best way of getting to that server so it can ask it for the number of the Gmail server.

This involves the cooperation of several other machines, called routers. From my home router, a packet of data travels to the Telstra router, to a central exchange then via other routers, to my DNS, similar to an air freighted package flying from Tamworth to Sydney then on to London via Dubai in a series of hops.

Here, the network sees that I’m at Emu Heights in Sydney, where my Telstra account connects. My query bounces around a few additional routers as the route is worked out and we end up at Fountain gate in Melbourne, the site for Kath, Kim and the DNS. It takes the cooperation of several machines to get there.

|

Hop

|

Name of machine (if known)

|

Machine IP address

|

|

1

|

10.0.1.1 (my machine)

|

(10.0.1.1)

|

|

2

|

gateway.nb02.sydney.asp.telstra.net

|

(58.162.26.66)

|

|

3

|

ae252.ken-ice301.sydney.telstra.net

|

(203.50.62.118)

|

|

4

|

bundle-ether25.ken-core10.sydney.telstra.net

|

(203.50.61.80)

|

|

5

|

bundle-ether1.ken-edge903.sydney.telstra.net

|

(203.50.11.173)

|

|

6

|

bundle-ether1.ken-edge903.sydney.telstra.net

|

(203.50.11.173)

|

|

7

|

one.one.one.one

|

(1.1.1.1)

|

So, six hops to my DNS (and back again) to find the address of the mail server, then, say, six hops from my machine to Gmail, then the merry dance continues to my friend’s BigPond server (another six hops) and from the BigPond server to his or her computer (another six hops) after my friend’s machine has worked out the address of their mail server (another 12 hops).

That’s 42 hops that the data has to traverse. It can be more, but we’ll go with 40 for ease of calculation.

Data on networks is divided into packets in the same way as a public transport system is divided into busloads or trainloads. Network packets are fairly small so that any corrupted data can be resent without having to send the whole message again.

Each packet is roughly 1500 bytes long. You’ve heard of bytes, right? One byte is approximately one character, so words like ‘email’ or ‘yo-yo’ are five bytes long.

As well as the text 'have a look at this cat video' and the video itself, we’re also sending metadata – data describing where the packet came from and where it is going to, which number in the sequence this packet is, how many packets are in the total message and some error-checking so that the receiving system knows whether it should request a resend of a packet. A typical email packet may have 15 bytes of metadata leaving 1250 bytes for the message itself.

So, how much data is in your average email?

In a 2019 study of marketing email, the average email length was roughly 3000 characters or 3000 bytes.

This will need three packets for data and the IP information. The last packet will be padded out to 1500 with zeroes.

An internet router sends around 400 million packets per second and uses roughly 4000 watts of electricity. Three packets sent via 40 hops is 120 packet transfers, each requiring 0.00001 watts giving a total of just over one-thousandth of a watt.

Not much, is it? But this is for one short email, with no pictures, or videos, or cute images in your email signature.

There are 3.7 billion email users worldwide, sending and receiving 74 trillion emails each day. (Just over 50 per cent of this is spam, by the way.)

I’ll do the arithmetic for you — it’s 74 megawatts per day (12 million tonnes of CO2 per year) — a pretty small amount of energy compared to the total earth budget.

Similar calculations show Facebook using 1,500 million tonnes of CO2 annually, with YouTube at around 80 times that.

Using similar calculations to those above, the internet used 10 per cent of global electricity in 2019.

Luckily, these organisations are increasingly sourcing their power from renewable resources.

Have you seen...

ACA resources for teachers?

The Australian Computing Academy (ACA) has many teacher resources available, including webinar recordings, teaching materials and assessment ideas. Visit the academy’s website to access the resources.

Keep in touch!

There are many ways to connect and keep in touch... the newsletter, DTiF Wiki and the Digital Technologies Hub. Do you follow ACARA? Join our growing social media community.

Tell us what you think!

Email us at [email protected]. We'd love to hear from you.